El

Museo Cicládico de Atenas ha albergado los días 1 y 2 el congreso

Cycladica in Crete: Cycladic and Cycladicizing figurines within their archaeological context, que ha tratado de profundizar en la relación de la isla de

Creta con el arte cicládico.

Mediterráneo Antiguo ha querido conocer con más profundidad algunos aspectos relacionados con este cautivador e interesante estilo artístico de la mano de la arqueóloga

Peggy Sotirakopoulou, una de las organizadoras del Congreso junto con el Profesor

Nikolaos Stampolidis, director del Museo, a quien ya entrevistamos en esta página con motivo de la exposición "Princesses of the Mediterranean in the dawn of History", celebrada en 2013. Aquí tenéis el contenido de la entrevista (en inglés).

Question - Normally we talk about several periods in the development of Cycladic Art. Could you explain us the main features of them?

Answer - The term Early Cycladic culture is used to define the first of the three periods into which the Bronze Age of the Cyclades is divided conventionally (Early Cycladic, Middle Cycladic and Late Cycladic). The

Early Cycladic period covers the interval from about 3200 to 2000 BC and on the basis of the development of the settlements and technical advances is divided into three sub-periods Early Cycladic I (c. 3200-2800/2700 BC), Early Cycladic II (c. 2800/2700-2300 BC) and Early Cycladic III (c. 2300-2000 BC).

|

Cycladic marble figurine from the cemetery at Koumasa, in south-central Crete. Photo: Museum of Cycladic Art |

EARLY CYCLADIC I PERIOD

Little is known of the settlements of the Early Cycladic I period. This is usually attributed to the fact that the houses of this phase were made of perishable materials, so that no remains have survived. It is equally likely, however, that this defective picture is due to the small size of the installations or to the fact that the building remains of this phase are not accessible, since they lie beneath buildings of later phases. Judging by the sites of the cemeteries of this phase, of which more is known, it may be concluded that the settlements were often located on hillsides or in plains near the sea, and more rarely in the interior of the islands. There were also settlements that occupied naturally defended sites near the sea. One of these, at Markiani on Amorgos, was further protected at its north, accessible side by a stout fortification wall with almost horseshoe-shaped bastions and an outwork in front of it.

The cemeteries are usually located on a hillside a short distance from the settlements to which they belonged and near the sea. Some cemeteries, however, are to be found on flat areas and in the interior of the islands. The graves were dug into the hillside and had an entrance facing downhill, which was the only feature defining their orientation. The majority of the cemeteries consist of 15 to 20 graves, usually arranged in clusters. Each cluster seems to have been used for the bodies of a single family. Features in the form of the ground, such as natural rock outcrops, served to separate the clusters and at the same time to protect the graves from erosion.

The commonest type of tomb was the cist grave – that is, each side of it was lined with a single upright slab of schist or marble. The plan of the graves varied, with a preference for a trapezoidal form. One, two or three extra slabs were used to cover the grave, and sometimes there was another placed on the bottom of it. In other cases, the graves were floored with pebbles set in clay. Quite frequently, a small rectangular slab was placed beneath the head of the deceased as a pillow. The greatest length of the graves ranges from 0.80 m. to 1.20 m. and their width from 0.30 m. to 0.80 m. They are usually shallow, varying from 0.30 m. to 0.60 m. in depth. The very small graves seem to have been intended for children. Above the covering slab was a small built platform, which seems to have served partly as a grave marker and partly for rituals held in honour of the dead. The grave markers could also take the form of a thin layer of pebbles set in a border of larger stones or of stones mixed with earth which formed piles, circles, semicircles or spirals over the capstone. The desire to mark the graves was also manifest when one of the upright slabs which lined the sides projected above the others, as a sema.

Each grave held only one body, normally placed on its right side in a tightly contracted posture, recalling the foetal position: knees strongly bent up to the chest, arms in front of the face, back facing the long side of the trapezium, and face towards the entrance to the grave. The contraction is occasionally so great that it is thought probable that it was achieved by binding the body with bands or ropes before rigor mortis set in. The highly contracted posture of the dead has sometimes been thought to be due to the small size of the graves; however, it seems that it was determined by a deep-rooted burial practice that is seen in the Aegean as early as the Mesolithic period. During the Early Bronze Age, this practice is widespread and, except the Cyclades, is also attested in mainland Greece and Crete, even in the cases that the tombs were spacious and held only one body.

The shapes of clay pots were limited in number. The clay is coarse-grained, contains many inclusions and is usually poorly fired, giving it a friable texture and a black core. The surface is brown or reddish and usually shiny as a result of mechanical burnishing with a pebble or a bone tool. The characteristic feature of the Early Cycladic I pottery is the incised decoration of thin, exclusively straight, densely arranged lines, forming either successive zones of herring-bone pattern, or rows of hatched triangles. The incisions are often filled with kaolin, the white mineral pigment found on Melos, which makes the designs stand out against the dark surface of the vases and creates a bichrome impression through the alternation of the white and dark.

Stone vases were made exclusively of marble and included a limited number of types. The main hallmark of these early creations is the faithful reproduction of specific types, with very few variations. Decoration on the surfaces of the vases is rare.

The figurines are of marble and fall into two basic categories: schematic and naturalistic: schematic figurines include very simple, usually small, flat ones with a roughly anthropomorphic outline, while naturalistic figurines include those in which there is an attempt at a naturalistic rendering of the human figure. Most of the Early Cycladic I figurines are schematic, the most common and best known of them being the violin-shaped figurine. The earliest of the naturalistic figurines, the Plastiras type, named after a cemetery on Paros, also makes its appearance in the Early Cycladic I period. To it belong standing male and female figures 7 to 31.5 cm high that are developments of the steatopygous figures of the Late Neolithic period. The distinctive features of the figurines of the Plastiras type are the meeting of the hands finger to finger beneath the breasts, very pronounced curves of the pelvis and thighs, legs that are separated for their full height, and a detailed rendering of the facial features and anatomical details of the body.

Metal artefacts were confined to a small number of bronze tools and jewellery from tombs on Naxos and Paros, a gold bead from a tomb on Naxos, and a few pieces of copper slag from the settlement at Avyssos on Paros.

![]() |

| Cycladic-type marble figurine from the cemetery at Koumasa in south-central Crete. Photo: Museum of Cycladic Art |

TRANSITIONAL EARLY CYCLADIC I-II PHASE

The transitional phase between Early Cycladic I and Early Cycladic II gives a clear indication of a significant development in metal-working and of emergent wealth and status evidenced by a number of bronze and silver artefacts found in two very rich tombs on Naxos and Amorgos.

Developments are also seen in pottery. New vase types and new techniques made their appearance alongside types and a decorative style that represent advanced forms of earlier ones. Narrow-necked vases made their appearance, as did the frying-pan vessel. The repertoire of the incised decoration was enriched by curvilinear motifs such as spirals and single or concentric circles, often rendered by deep incisions filled with kaolin. The technique of impressed decoration was also introduced, in which the designs are not incised but impressed on the surface of the vase with a wooden stamp. The repertoire of impressed decoration includes spirals, single or concentric circles, and rows of triangles forming relief lozenges or relief zigzags. Finally, the technique of covering the entire surface of the vase with a shiny red glaze, known as Urfirnis, also makes its appearance; this is a paste of thin, clear clay which on account of the content of argil in some of the constituents, forms a lustrous layer on the surface of the vase during firing.

This phase is also characterised by a distinct tendency to experiment on the part of the Cycladic sculptors, and by the emergence of a large variety of figurine types, which seem to reflect the aspirations of the period. To this phase belong the Louros and hybrid types, which are intermediate between the schematic and naturalistic, and the precanonical type. The Louros type, which owes its name to a very rich tomb at Louroson Naxos, comprises figurines that are distinguished by the abstract treatment of the human figure, with a triangular or amygdaloid head tilted slightly backwards, schematic rendering of the arms with wing-like protrusions on the shoulders, an attempt at a plastic rendering of the legs, horizontal feet, and a complete absence of facial characteristics and, usually, anatomical details. The precanonical type includes figures that, while retaining certain characteristics of the Plastiras type – such as the upright stance, detailed facial and anatomical features, curvaceous pelvis and thighs, separated legs, and plastic rendering of the different body parts –, at the same time exhibit elements that are forerunners of the so-called canonical figurines of the Early Cycladic II period, such as the backwards tilt of the head, the first efforts to render folded arms, with one forearm above the other, and the bending of the legs.

The rock-cut tombs found on Ano Kouphonisi also date from the transitional phase between Early Cycladic I and Early Cycladic II. These tombs were cut into the soft limestone bedrock and comprised two parts: one open outer part (prothalamos), trapezoidal or oval in plan, and one roofed inner part that comprised the main funerary chamber (thalamos). Their size was large by Cycladic standards, and the forecourts larger and deeper than the main chambers. The corpse was placed in a contracted posture with the head towards the entrance of the burial chamber. After the interment had taken place, the entrance to the funerary chamber was blocked by a large upright slab that sometimes protruded above the original ground surface, as a grave marker, and the forecourt was filled with two subsequent layers of earth and stones up to the original ground surface.

EARLY CYCLADIC II PERIOD

The architectural remains multiply during the Early Cycladic II period. The settlements of this phase are sometimes on promontories and sometimes on low hills or naturally defended sites by the sea, though there were also settlements in the interior of the islands. Some of them are fortified, while others have so far yielded no signs of fortifications during the Early Bronze Age. Their size varies, ranging from 0.3 hectares at Markiani on Amorgos to 1.1 hectares at Skarkos on Ios.

The cemeteries are larger than in Early Cycladic I and the cist grave continues to be the commonest type of tomb. However, single-chamber cist graves are now used for multiple successive burials of members of the same family. This phenomenon points to an increase in the population, or at least its concentration in larger settlements. As a consequence of this practice, graves ceased to be organised in clusters and their entrance was no longer sealed by a stone slab, but by dry stone walling, so that they could be opened easily for each fresh interment. Beneath the stone slab on the floor, one or two storeys were often created to serve as ossuaries. Every time space was required for a new interment, the bones of the previous body were moved to one end of the grave or placed in one of the lower storeys, though the skull was normally left in its original position. This special treatment reserved for the skulls of previous burials suggests respect for the head as the centre of human existence.

Another type of tomb used in this period is the corbelled grave, which has been found only at the cemetery at Chalandriani on Syros. This is the largest Early Cycladic cemetery, differing greatly from the rest in that it has over 600 graves. The graves in it were small chambers cut into the side of the hill, with their sides lined with dry stone walling consisting of small stone slabs corbelled in: that is, each course of stones was laid slightly further in than the one below it, so that the opening was gradually reduced, and finally sealed by a single slab. The token entrance to the grave was sealed by dry stone walling or a single vertical slab, and took the form of a house door, with jambs, lintel and threshold. There was usually a small dromos in front of the entrance. The ground-plan of the graves varied in shape, and might be quadrilateral, circular or elliptical, polygonal, or completely irregular. These graves held a single body each and were therefore organised in clusters, as in the earlier cemeteries. Interment was carried out through the roof of the grave and the body was placed on its left side, in contrast with the practice known in cist graves.

Pottery-making reached its pinnacle in Early Cycladic II, during which it was characterised by a wide variety of vase shapes and decoration. Several shapes evolved from earlier ones, though new shapes also made their appearance. The innovations of the transitional Early Cycladic I-II phase became the hallmarks of this phase. Earlier techniques, however, such as the mechanical burnishing of the slip, and the use of incised decoration, continued in use. The processing of the clay was perfected so that it was now almost pure with no coarse inclusions, and the firing was improved, making it possible to manufacture vases with thin walls and flexible outlines, which often seem to have been influenced by metal vessels. The innovations of this phase include spouted vases with a raised spout in the shape of a bird’s beak. Familiarity with the use of Urfirnis led to the technique of painted decoration, another innovation of this phase. The surface of the vase is covered with a light slip, on which are painted dark rectilinear or curvilinear designs arranged in horizontal or vertical zones; representations of birds, quadrupeds and fish are also found.

Stone-working reached great heights in both a technical and typological sense. All the early types continued to be made, though renewed and in different varieties, while at the same time a series of new ones made their appearance which either copied ceramic shapes of this period or were completely original. This is perhaps not unconnected with the development and wide application of metalworking, which supplied the craftsmen with more durable and effective tools. A tendency towards diversity and variety in the form is characteristic of this period and stemmed from the craftsmen’s freedom of expression. The sizes of vases are small, their walls thin, verging on translucent, and the lines curved. Many marble vases stand on a high, trumpet-shaped foot which, as in the pottery, is a distinctive feature of this period. Occasionally, veined marble was used instead of white, with the veins following and emphasising the outlines of the vases. Alongside marble, use was made of coloured limestones, particularly for simple types, soft chloritic schist, especially in composite shapes, as well as white limestone and schist, for coarse palettes-grinding vessels for household use. Some types of marble vases often have incised decoration consisting mainly of rectilinear and more rarely of curvilinear or pictorial motifs. Decoration is most common on vases made of chloritic schist, which are sometimes incised with rectilinear motifs and sometimes worked in relief with curvilinear designs. Examples are also known of marble vases that preserve traces of red-painted decoration of simple linear motifs.

The marble figurines are both schematic, of the so-called Apeiranthos type, and naturalistic, of the canonical folded-arm type, which is the best known and most numerous category of Cycladic figurines and the characteristic hallmark of Early Cycladic II. The long life of this type, which continued to be found virtually unchanged for about five centuries, is impressive, though we do not know if the meaning of the figurines also remained unchanged. Their height varies dramatically, from the smallest at 7 cm to 1.50 m for the largest monumental examples, which are close to life-size, though these are relatively few. The canonical figurines normally depict nude female figures, though a number of male ones are also found. The figurines of this type have a number of basic characteristics: the head is tilted backwards and ends in a flat surface that seems to symbolise some kind of headcover or special coiffure. Of the facial features, the nose is always modelled. Some of the large sculptures also have modelled ears, while the hair, eyes and eyebrows are indicated by paint. The mouth is usually omitted, a feature that may have a symbolic meaning. The breasts are shown in relief. The arms are folded beneath the breasts in what is called the “canonical arrangement” – that is, with the right forearm beneath the left. The pubic triangle is in many cases incised. The legs are joined and usually slightly bent at the knees. The feet usually slope downwards, giving the impression that the figures are standing on the tips of their toes. The spine, knees, ankles, fingers and toes are often indicated by incisions, though the number of fingers or toes is not always correct.

The early phase of Early Cycladic II has also yielded a relatively small group of elaborate special figure types. Though typologically associated with the canonical figurines, these have broken free of the strict frontality of those figures and have acquired a third dimension. They include standing and seated male figures engaged in some activity (such as musicians and the cup bearer), seated female figures in a passive stance, and compositions of two or three figures.

The Early Cycladic II period is also characterised by the great development of metallurgy and metalworking in the islands. Two types of bronze weapon are thought to have been invented by the Cycladic islanders: (a) the type of the tangless double-edged dagger, with a relief midrib along the entire length of the blade and two or four holes to attach it to a wooden or bone handle by means of bronze or silver rivets, and (b), the type of the spearhead with a relief midrib, plain tang and two elongated slots to attach it to the shaft. There are also a wide variety of cosmetic instruments of bronze, jewellery made of bronze, silver, bone, semi-precious stones and seashells, a few silver vessels and a small number of artefacts made of lead.

![]() |

| Head of Cycladic-type marble figurine from the cemetery at Phourni, Archanes in north-central Crete. Photo: Museum of Cycladic Art |

EARLY CYCLADIC III PERIOD

Towards the end of Early Cycladic II, a set of new, mainly drinking and pouring shapes appeared in the Cyclades and on the eastern coasts of mainland Greece, with a characteristic dark – black, brown or red –, highly burnished surface, which seem to derive their origins from various areas of Asia Minor. These new shapes form the so-called Kastri group. The use of the potter’s wheel and of a copper-tin alloy were also introduced from the East during this period. Recent evidence has shown the Kastri group pottery to occur side by side with that of the Early Cycladic III period, thus indicating that the two phases overlap for the most part.

The Early Cycladic III pottery is largely a continuation or development of that of the previous phases. At the same time, however, new vase shapes and decoration made their appearance. This pottery is best known from Phylakopi, where it occurs in two styles: one with a shiny dark surface (red, brown or black) and incised decoration with both rectilinear and curvilinear designs, and the other with dark painted decoration on a thin white slip with motifs that are as a rule rectilinear and only occasionally curvilinear. At the end of this phase, the use of curvilinear motifs began to dominate and pottery with white painted decoration on a dark surface made its appearance.

During this period an appreciable reduction in the number of settlements is observed. Cist graves continue in use, as also do the corbelled graves on Syros. On the volcanic island of Melos, where the ground was conducive to rock-cut structures, rock-cut tombs have been discovered at various sites but they are best known from Phylakopi. These consisted of one or two adjacent chambers cut underground, with an entrance, a sloping dromos and occasionally a pitched roof. The burial chambers were quite large. Their ground-plan varied in shape, and might be rectilinear, trapezoidal, elliptical or circular. Most of the Phylakopi tombs had been plundered, therefore the number of bodies they contained is unknown. However, it seems that they were intended for multiple successive burials. In addition, infant jar burials both inside and outside the settlement reappear in this period for the first time after the Final Neolithic. Marble sculpture has a marked decline. The figurines of this period are schematic and belong to two types named after the sites at which they have been found: the Phylakopi I or Ayia Irini type and the Dhaskalio sub-variety.

Question - What is the influence area of the Cycladic Art?

Answer - The archaeological evidence indicates that the Cyclades developed relations with the rest of the Aegean world at a very early date. Already at the end of the Palaeolithic (11th millennium BC), and throughout the Mesolithic period, the eastern coasts of the Peloponnese and the islands of the north and east Aegean procured obsidian from Melos. During the first stages of the Neolithic (7th millennium BC), Melian kaolin, used in the manufacture of pottery in the special category of “all-white” vases, and millstones from the islands travelled to mainland Greece in addition to obsidian which during this period reached as far as Thessaly and Crete. Contacts between the Cyclades and other Aegean areas intensified in the Late Neolithic period (c. 5300-3200 BC) to include Cycladic types of marble vessels in Samos and in the Troad, and reached their apogee during the Early Bronze Age (3rd millennium BC), in particular during the Early Cycladic II and III periods, when they extended from Macedonia to Crete and from Lefkas in the Ionian Sea to the interior of Western Asia Minor and Cyprus. The Cycladic influence on other areas takes the form of both imported raw materials (such as obsidian from Melos, copper from Kythnos, silver and lead from Siphnos, and, of course, marble, the main raw material of the islands) and finished products (such as clay and marble vases, marble figurines, silver vessels, tools and jewellery, bronze tools and weapons, bone tubes-pigment cases and seal impressions), which are either directly imported or imitated in these areas. The contacts of the Cyclades with the various Aegean areas could have been both direct and indirect; in the latter case, it was most probably through trading centers on the coasts that Cycladic artefacts would be redistributed to further or inland areas to the north, east, west and south. The widespread occurrence of Cycladic or Cycladicizing creations in other Aegean areas attests both to their appeal as objects of prestige and social differentiation and to the fact that the transit trade was conducted for the most part by the seafarers of the Cyclades.

Moreover, in some cemeteries on the coasts of Attica, Western Asia Minor and North Crete not only Cycladic-type grave offerings have been found, but also types of tombs and burial practices similar to those of the Cyclades. For this reason, these sites have been interpreted by scholars from time to time as “Cycladic colonies”. However, the degree of Cycladic influence at these sites is not the same, and the phenomenon should therefore be interpreted differently in each case. Haghia Photia and Gournes on the coast of north Crete, where the architecture of the tombs and burial customs are foreign to Crete and have close parallels in the Cyclades, and the vast majority of the grave offerings are of Cycladic style or origins, seem to be the only cemetery sites at present at which there are grounds for speaking of the settlement of people from the Cyclades in late Early Cycladic I and in the transitional Early Cycladic I-II phase. Another such site is thought to have been the Minoan gateway port at Poros-Katsambas in the harbour district of Herakleion, where not only large quantities of Cycladic or Cycladic-type pottery, metals and obsidian have been found but the new skilled Cycladic technology necessary for working metals has also been imported.

Question - Which were the main production centers?

Answer - The evidence for the production of various sorts of artefacts which is cited below does not necessarily mean that the sites or islands mentioned are the main production centres. Several of them may have not been identified or come to light as yet.

Regarding production of marble artefacts: Non-invasive optical examination and isotopic analysis of Early Cycladic marble artefacts have demonstrated that the marble came mainly from Naxos and to a lesser extent from Paros and Ios. Vases and figurines were occasionally made of other kinds of stone and/or other materials, though the number of these objects is very small compared with the marble artefacts. Only one stone-mason’s workshop has been identified so far, at the Early Cycladic II settlement at Skarkos on Ios.

Regarding metalworking and production of metal objects: Copper ores were collected from Kythnos, Seriphos, Siphnos, Lavrion and perhaps Kea, and smelted on Kythnos and at Chrysokamino in Crete. Copper smelting was also taking place at Kavos promontory on Keros and possibly on Seriphos and Kea too. The most interesting copper smelting site in the Cyclades proved to be the site of Skouries on Kythnos, where smelting facilities have been located as well as remains of kilns of the Early Cycladic II period. In Early Cycladic I-II the overwhelming majority of Cycladic copper-based artefacts was made from relatively local copper ores occurring on Kythnos, Siphnos, Seriphos, and in Lavrion, but copper from Cyprus and from deposits in the Taurus Mountains and on the Black Sea coast also appear in small quantities. The quantities of Cypriot and Anatolian copper circulating on the Cyclades increased markedly in late Early Cycladic II and Early Cycladic III period, which indicates lively and increasing contacts with the eastern and southeast Mediterranean in the late 3rd millennium BC.

Lead isotope analysis of metal artefacts of the Aegean Early Bronze Age has also shown that the two main sources of silver in the Aegean were Siphnos and Lavrion. In Early Cycladic I-II, the majority of Cycladic lead and silver artefacts was made from the lead/silver ores either of Siphnos or of Lavrion, but metals from the two silver mines in northwest Asia Minor are also present. The quantities of lead from Asia Minor increase markedly in late Early Cycladic II and Early Cycladic III, a feature which parallels the increase in procurement of copper from the east during the same period.

Although many seams of arsenical copper and argentiferous lead have been located in the Cyclades, the only convincing evidence so far for the quarrying of metals in the islands during the Early Bronze Age comes from the mines of argentiferous lead at Ayios Sostis on Siphnos. Smelting was carried out in depressions in the ground near the mines, to avoid transporting large quantities of metal over long distances. The smelting of the argentiferous lead ores yielded argentiferous lead, from which silver was then produced by cupellation. Lead that proved after a small trial cupellation to contain only a small quantity of silver was used to make lead objects. Similar processes were followed to extract and smelt copper-bearing ores.

The end-products were made in the settlements, in which there was probably a separate class of metal-craftsmen. Copper/bronze weapons and tools were cast in open moulds and then forged to give them their final form. Jewellery – bronze, silver and rarely gold –, like silver vases, was made of sheet metal. Clear evidence for metalworking has so far been found at the settlements of Kastri on Syros and Dhaskalio on Keros, in levels of late Early Cycladic II and Early Cycladic III date. At Kastri, one room contained a hearth with pieces of copper slag, an assemblage of bronze objects, obsidian blades, one with metal dross stuck to it, small stone spool-shaped pestles and one clay crucible for smelting the metal. Further evidence that metalworking was practised in the settlement is provided by the occurrence of three more clay crucibles with remains of copper or lead slag on the inside walls and two open moulds, one made of clay and one (double-sided) of schist, for casting weapons and tools. A number of bronze tools or weapons, such as axes and a spearhead, lead clamps for repairing broken vases, and a silver diadem with dot-repoussé decoration of birds, quadrupeds and star-shaped ornaments were also found in the settlement. Dhaskalio has yielded some metal objects and modest indications of metal production, probably casting rather than smelting. These include three substantial copper/bronze objects (an almost flat axe or chisel, a shaft-hole axe and an axe-adze), now termed the “Dhaskalio hoard”, a lead cylinder or weight, splashes of copper on stone, three ceramic tuyères, a small shaft-hole hammer of lead that may have been used in metalworking, and lead clamps to repair pottery.

Regarding working of obsidian: Certain rooms in the settlements, in which groups of spindle whorls, obsidian débitage, metal objects, fine stone pestles, storage jars and stone grinding vessels were found, were presumably used for weaving, working obsidian, the storage and preparation of food, and various other activities related to production and subsistence. However, obsidian blades are a regular component of both settlement and burial assemblages in the Early Bronze Age Cyclades. The funerary consumption of obsidian becomes more popular in late Early Cycladic I and even more so in Early Cycladic II, when multiple-blade assemblages occur in graves and the length of the blades being buried reach as much as 22.5 cm in length. The exceptional length of these blades is considered to be the result of their having been manufactured by a new and highly skilled technology that was developed for and restricted to the burial arena, a phenomenon that Carter has termed the “necrolithic”. Evidence for the production of blades in burial places for funerary use is provided by the presence in some graves of obsidian blades in fragmentary condition or remarkably fresh and mostly unused and of obsidian flakes which may represent debitage from a blade production process, as well as by the fact that both blades and manufacturing debris of obsidian are sometimes found in cemetery areas outside graves.

Regarding production of pottery: Fabric analyses of Early Cycladic pottery indicate that a number of ceramic pots were made out of locally available clays and others were imported both from neighbouring and distant areas. However, only one pottery kiln of this period has been found so far, at the settlement at Ayia Irini on Kea.

![]() |

| Cycladic-type marble figurine from the cemetery at Phourni, Archanes in north-central Crete. Photo: Museum of Cycladic Art |

Question - Regarding to the relation with Crete, where are the main archaeological sites inside the influence of Cycladic Art in the island?

Answer - Objects of Cycladic provenance or inspiration have been mainly found in north-central and south-central Crete (that is, in the Herakleion Prefecture) and at the north coast of eastern Crete (Lasithi Prefecture). However, sporadic Cycladic or Cycladicizing finds have also been made in the western part of the island, that is, in the Rethymno and Chania Prefectures. (Note that the terms “Cycladic-type”, “Cycladicizing”, and “of Cycladic inspiration” stand for local copies or imitations of Cycladic prototypes). The names of the sites where such objects have been found you can find in the titles of the papers to be given in our Symposium.

Question - How did Cycladic Art arrive to Crete?

Answer - Raw materials and artefacts of Cycladic provenance reached the north coast of Crete through trade, which, as noted in answer no. 2 above, is believed to have been mainly conducted by the seafarers of the Cyclades. Thence, they would be redistributed further to the east, west and south. However, as also noted in answer no. 2, the cemetery sites at Haghia Photia in east Crete and at Gournes to the east of Herakleion, and the Minoan gateway port at Poros-Katsambas in the harbour district of Herakleion, are thought to indicate settlements of Cycladic people in late Early Cycladic I and in the transitional Early Cycladic I-II period.

Question - What tell us the last archaeological investigations about the interpretation of this sculptures?

Answer - According to the most recent views, marble Cycladic figurines were prestige objects with a diversity of meaning and use: they were used, that is, in all rituals that marked the definitive stages of an individual’s life, such as entry into adolescence, marriage and death, and also in rituals in honour of ancestors, which were essential to the survival of the small Cycladic communities and were aimed at asserting their cultural identity. Thus, it has been suggested the figurines were given different painted decoration on different occasions, depending on the symbolic role they were called upon to play.

The absence of written sources and evidence from securely excavated contexts relating to religion and the practice of cult in the prehistoric Cyclades, combined with the fact that a large proportion of Cycladic figurines have come from illicit excavations, inevitably confines the various views on their significance and use to the level of mere conjecture. Their presence in both tombs and settlements certainly undermines the view that they were intended exclusively for funerary purposes, and supports the probability that they were also used in daily life for ritual purposes. Moreover, the fact that in some cases marble figures broken into pieces, or fragments of figures broken in antiquity, have been found inside or outside tombs, in settlements and in areas of what appears to have been a ritual deposition suggests the performing of rituals during the course of which objects of high symbolic significance were deliberately broken.

Question - Cycladic Art was very appreciated in the past, how far from the centre have been found sculptures or objects linked to this style?

Answer - The extent to which Cycladic raw materials and Cycladic or Cycladicizing artefacts are distributed is given in answer no. 2 above. Regarding the Cycladic and Cycladic-type marble sculptures in particular, they are found from Skyros in north Aegean to the Mesara plain in south Crete, and from Elis in western Peloponnese to Miletus on the western coast of Asia Minor.

Question - What will be the mainlines of the Congress?

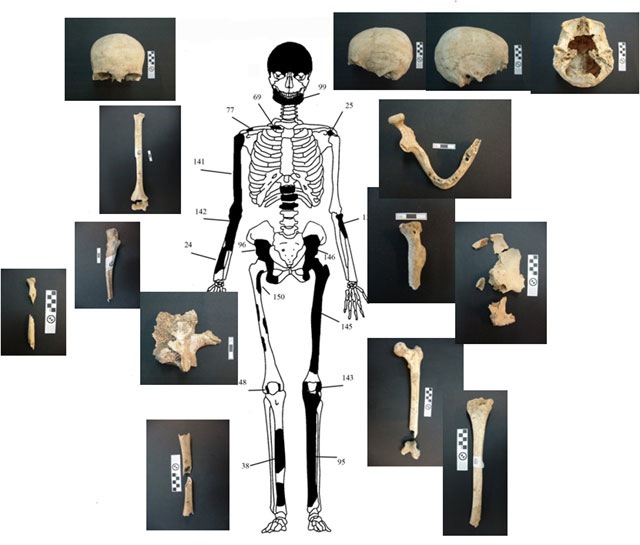

Answer - Crete has produced the largest number of Cycladic and Cycladic-type figurines from all the other areas of the Aegean: about 90 such sculptures, both complete and fragmentary, from well documented archaeological contexts have been located so far. A number of them have been identified as direct imports from the Cyclades, while the rest are considered as local imitations of Cycladic prototypes. This taken together with the fact that the Cycladic or Cycladicizing figurines are not only deposited together with other Minoan, Cycladic or Cycladic-type offerings in purely Early Minoan contexts but are also smashed in the way they are in Early Cycladic sites leads to the conclusion that these objects were not simply imported or copied in Crete as objects of prestige and social differentiation but also conveyed the symbolic meaning they had been assigned in the Cyclades. So the discussion of the entire body of this material together with the other associated finds within their archaeological context is hoped to illuminate in light of modern research the sort of relations between the Cyclades and Crete during the 3rd millennium BC.

Author

Mario Agudo Villanueva